Wanderlust: In Conversation with Chef Imrun Texeira

Like many others, Restaurants Canada’s One To Watch award winner Chef Imrun Texeira’s career was rudely interrupted by the pandemic. But that’s where comparisons end.

Just prior to the arrival of COVID-19, having just finished as a semi-finalist on Top Chef Canada, he pulled up stakes, sold his possessions and embarked on a well-planned journey that promised to take him through the great kitchens of the UK, Europe and Asia. In mere months, he lost everything.

We met with Imrun to learn how, through the launch of his new luxury private chef service, Wanderlust, his most bitter disappointment has led him to a period of self-realization and clarity and inspired a commitment to helping transform the future of the industry while recasting his own.

MENU: Let’s start with your origin story—why did you choose to become a chef, and what experiences along the way have shaped your journey?

I became a chef mainly because I liked eating and being around good food. I wanted to cut out the middleman—I knew that if I could cook good food, I’d be surrounded by it my whole life. I had the opportunity at a very young age to see what the fine dining world had to offer. Food was always a big part of my life and I’ve always had an interest, passion and love for it, but I’ll always remember that initial meal. I must have been like, maybe eight or nine years old and I remember going into this beautiful hotel for a family meal and sitting down at a table with white tablecloths, impeccable service and an absolutely gorgeous dining room. Dessert was a chocolate mousse and we were given a spoon made out of sugar to eat it. That you were able to create a spoon out of sugar and then eat the spoon after just blew my mind. To be honest, if I saw that now it would still blow my mind.

The kind of creativity that’s out there when it comes to food, in general, is super cool and probably what really kick-started my passion and led me—out of necessity—to my first job. My parents eventually divorced and I found myself growing up in the Ottawa area with a single mother of four. It wasn’t easy for her, so my siblings and I had to do what we had to do to take some pressure off her shoulders. I got my first job at 14 years old at a local chain restaurant. It was driven by necessity, but partly fueled by curiosity.

I’ve always been ambitious and had a business mindset from a young age. I started lemonade stands and car washing businesses; I cut people’s grass—anything a 12 to 14 year-old could possibly think to do. When I landed that first restaurant job, they assumed I was about 16, but found out my real age on my birthday after I’d been there for about a year. You don’t see too many kids around that age working at these kinds of establishments, so I was very lucky to get that job.

After that, I took a role at a full-service chain restaurant. That’s where I got a little more insight into the mechanics of the industry and the good and the bad of what it had to offer. It was not glamorous and was not the best place to learn life skills. I was doing dishes, which, I think we can all admit, kind of sucks. But that was my way in and seeing the atmosphere of the kitchen, the adrenaline that comes from a busy Friday or Saturday night service and then meeting people from various backgrounds and ages was a pure adrenaline rush. I absolutely loved it. The dish pit parlayed into other roles and in about six months I got on the line making quesadillas, chicken wings, and nachos—very basic stuff. I was able to get on the line and start cooking with my older brother, and cooks ranging 10 to 30 years older than me. It was a pretty wild experience.

MENU: So, you’re an ambitious kid who finds himself among cooks and then formally trained chefs at a very young age. How were you treated?

When you’re working in chain restaurants, there are obviously a lot more teenagers and young professionals just going through the ranks and coming in and out of the place. So I did get thrown in the dumpster or stuff thrown at me as sort of little hazings as has been known to happen in the industry. It’s definitely not right, but at the time, I just thought of it as part of the process. On Friday or Saturday nights, cooks would pay me extra money to finish their shifts so they could leave and go out. It worked for me at the time.

When I got my next job at a family-owned Spanish wine and tapas bar, management recognized I had a passion for the role. Then, at 16 or 17 I took on a co-op and youth apprenticeship program at the Brookstreet Hotel in Kanata, the same hotel where I experienced that incredible meal. From there things just really flourished. I was working more junior roles, but I stayed after hours to work the night service when they did tasting menus, they had guest chefs and big charity events. I just wanted to learn as much as possible and they took really good care of me and took me under their wing. That job is what built my foundation and my fundamental skills now. It was just a great time to be at that hotel, probably at one of the best times in Ottawa for the reputation of the hotel and the restaurant there and working with chefs that have trained for years and who saw my passion and offered me nothing but love and respect in return.

MENU: As a person of many skills and interests, you had a lot of options in terms of your career. Was your experience at Brookstreet what made you decide to commit to the industry?

The youth apprenticeship at Brookstreet was a result of a push from my high school guidance counselor. At that time, being a chef was just confirmed as a Red Seal trade in Canada. She explained it would help move me forward faster and we completed the paperwork, but it mostly went over my head at the time—I just wanted to get into the kitchen. Ultimately, I enrolled in culinary school at Algonquin College in Ottawa, which actually wasn’t my first choice. I had originally signed up for Police Foundations, planning to do a concurrent accelerated program in Psychology at Carleton University. I wanted to join CSIS and work as a behavioural analyst. Criminal Minds was probably one of my favourite shows growing up, so I always had that kind of interest.

In spite of the best-laid plans, everything I did just kept pulling me back to the kitchen, and I came to a realization within that first semester. Cooking is what’s meant for me. A year later I enrolled in the culinary apprenticeship program and I was able to finish the whole program within six months because of my past experience and youth apprenticeship. The chefs at the college saw that experience and gave me more responsibility and peer mentorship roles. They took me along on events and pop-ups, so I was able to really build an amazing network. Because of those teachers and connections, I got to work at some of the best fine dining restaurants within the Ottawa area ranging from French to Spanish, Mexican, vegan food—all the way up to Atelier.

MENU: Is that where you started to find your culinary style?

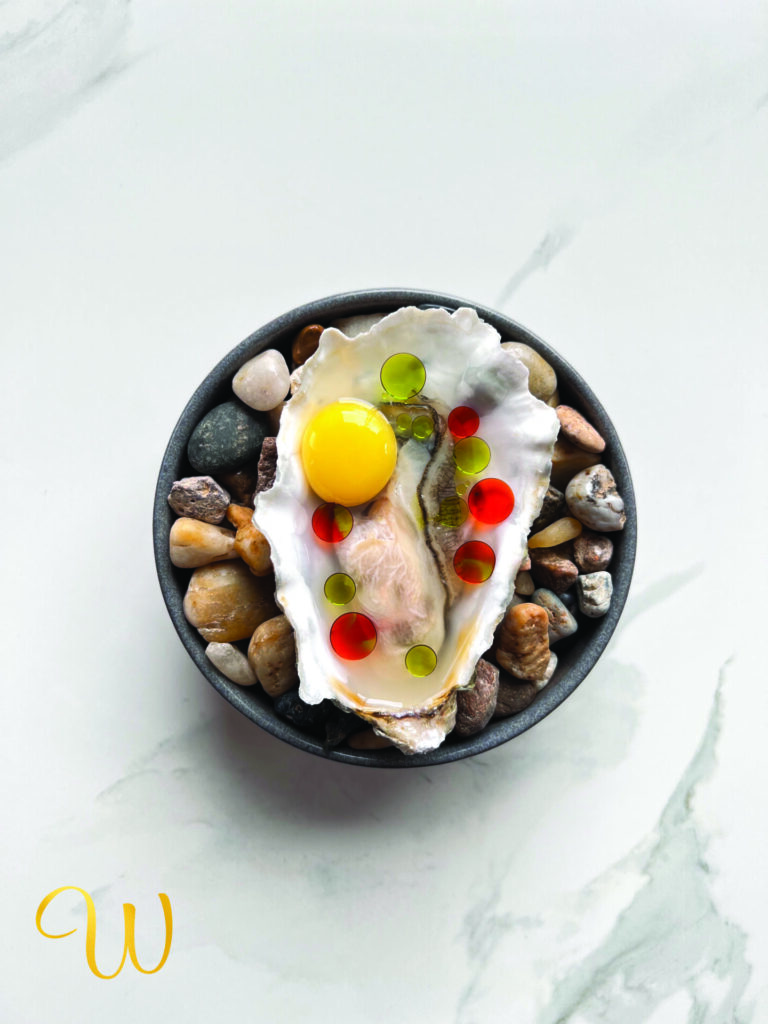

At Atelier, we had a twelve-course blind-tasting menu. We focused on molecular gastronomy, so cutting edge techniques and food styles that were rare around the world and completely unseen in Canada. It took me back to the moment I saw the edible sugar spoon at Brookstreet. I did a stage at Atelier, and I saw the edible helium balloon. It blew my mind once again. For me, it’s always been that creativity, that curiosity. These are things many of us lose coming out of childhood in a sense, but to this day I still haven’t lost that.

Atelier was a big turning point for me. I was there in 2016, a year or two after graduating culinary school. Within a few months, I was putting dishes on the menu, which, at 14 years old, I never would have dared thought I’d be at a place of that calibre so quickly, working with a renowned Canadian chef like Marc Lepine at what was probably the peak of that restaurant prior to COVID. It’s mind blowing to look back on that journey.

MENU: So what drew you to Europe—curiosity, ambition or a bit of both?

I always had sights on the Michelin Guide; the top restaurants. So in between working stints in Ontario, I had time to go to England and stage at some of the top Michelin-rated restaurants. I went to learn the top chefs’ styles and techniques and to gain insight into what the Michelin circuit really had to offer in that country. I loved it. Obviously, it’s become apparent that there are parts of it that aren’t sustainable, but no matter what I do, I’ve always pushed myself to work at the highest level and push to be the best in my realm.

MENU: So is the pursuit of that “Michelin discipline” embedded in your most recent venture, Wanderlust? Are you hoping to ascend to that level of excellence, but within a new format?

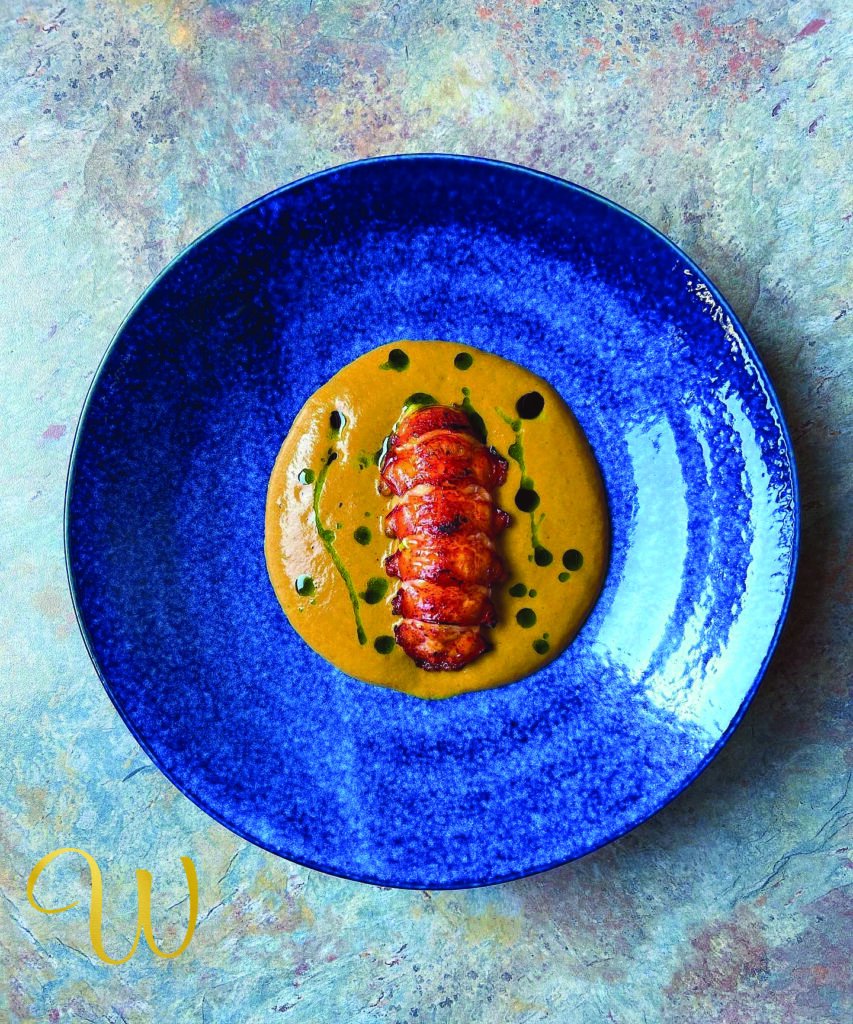

To be honest, that’s the exact idea. I’ve been very lucky and fortunate to travel around the world and eat at Michelin Star ramen places in Japan, or Michelin Star noodle places in Hong Kong. You see street stalls with these kinds of accolades running a similar version of the business model. If these street stalls or other non-traditional, white-glove-level restaurants can gain this kind of respect, why can’t I be the first chef without a restaurant space to have a Michelin Star? Why can’t I still offer that level of dining, that level of creativity and that level of hospitality? A lot of private chef work is doing exactly what the client wants, but I try and take that control away based on my creativity and the expertise that I’ve built over 15 plus years. I take that full creative freedom and offer an experience that no one’s really done ever before, at that highest level.

MENU: So, with Wanderlust, you’ve expanded your margin potential by eliminating overhead and emphasizing your craft, placing your food—and yourself—at the centre of the experience. You could do a dinner in someone’s home, in an abandoned warehouse or in a back alley, but you remain devoted to the highest level of culinary and service excellence.

Yes, and that’s the hardest part. It’s not like there’s a manual. I’m still under 30 with a good base skill set, but in the grand scheme of things, I’m aware that I’m only just starting to run my own business in a city that I’ve never worked in professionally. I’m building a new network, building a new business, and plus all the other work I’m trying to do to better the industry. It’s a full plate.

Coming out of COVID, I’d lost momentum, money and resources, but now, I’ve taken on so much and I feel like there’s going to be so much growth in the hospitality and food industry. There are new ways to push the envelope of what experiences and hospitality can be outside of the more traditional models and still make money. Here in Toronto, you’re not always going to have to go down to Yorkville to sit in the nicest dining rooms and have the best meals. I have had better food and better experiences at these different holes in the wall within the GTA or at pop-up events and on farms and B&Bs scattered around Ontario.

What I do with Wanderlust isn’t the cheapest by any means, but you’re paying for good products. I charge what the service actually costs and the people I bring on for the events all get paid a good living wage.

MENU: You went from a surreal career high with roles at Noma, your run on Top Chef Canada—the world was your oyster. Then the pandemic arrived and flatlined that incredible upward momentum. When we talk about mental health in this industry, perhaps we don’t talk enough about the extraordinary discipline and effort that goes into building a breakout career. That must have been devastating for you.

Obviously COVID played a big part in so many things and it hit me very hard. In late 2019 after filming Top Chef Canada, I sold 90 per cent of my belongings and my car and packed up what I had left here in storage to move to England. I was working at some amazing places there, and had internships set up in central London, obviously at Noma and at places in Dublin. I was supposed to do a master class apprenticeship in Italy for a few months as well, eventually trying to get down to Australia to work in foodie capitals there. Then, everything went to s—t.

I was on a massive trajectory and was basically slapped in the face with this pandemic. I had to relocate to Toronto, I’d lost my money and had nowhere to work. I tried to get part-time work as a butcher, a baker—but they wouldn’t hire me—maybe because I was overqualified, who knows? I’m used to working five, six days a week, 14-16 hours days. Going from that pace to doing nothing was extremely difficult and took a mental toll.

MENU: Many in the industry experienced a kind of epiphany in terms of their career direction during the pandemic. How did these experiences change you or your perspective?

A lot of the restaurants that I’ve worked at, especially fine dining, are focused on Western flavours and techniques focused on Spanish, French or Italian cuisine. I started to question why my cultural cuisine, or flavours from the East or South America are not represented at that level. However, working at these fine dining restaurants, I noticed that I was often the only Person of Colour in the kitchen (especially among those of higher professional rank). It was also interesting that when the kitchen staff went out to eat on days off or after service, we were all eating food from my culture or other cultures not showcased in the “great” restaurants. I’ve worked at some of these amazing places in this country where I’ve been able to put my dishes on menus and they say, “We can’t use that kind of level of spice.” or “We can’t use that kind of protein because these things aren’t going to sell; people aren’t going to like that.” Well, I come from a part of the world where there’s a billion people in one country that can eat this day-in and day-out, so I know there’s money that can be made from this.

I’ve always been told to tone down who I am. Not in the grander sense of who I am individually, but in what I’m trying to showcase. I’ve always felt that hindrance or that setback and I’ve always just wanted to destroy all that noise and have full creative freedom. With Wanderlust, I have found a way to do what I do. I’m not here to do burgers and sliders or massive corporate events. That’s not where my passion lies. I’ve been doing blind tasting menus for so long; I’m not trying to lose that. I’m trying to showcase that it’s a viable career and business model that gives you creative freedom. My clients are people who make decisions around the clock—they have decision fatigue. So, the only decision they have to make for a special, intimate gastronomic experience is calling me.

All of the events have gone over amazingly well, and it’s a lot of fun for me. I have missed working with a brigade and having people come to you—there’s definitely a learning curve to building a Michelin Star kitchen in somebody’s home. We’re in the most multicultural city in the world and most multicultural country in the world, and I’m taking people on a ten-course journey around the world to instill that feeling of wanderlust—that feeling of the everlasting, traveling restaurant. It’s never going to be in the same spot. You have to be there. You have to experience it because it’s never going to be exactly the same. I think there’s something beautiful about that.

I’ve taken on the challenge in exchange for the freedom to design menus that pull in techniques, flavours and ingredients I’ve traveled the world to explore, bring back and help showcase. I think this is the new Canadian cuisine.

MENU: There has been a growing chorus of voices in the industry refuting the validity of the long-accepted “rules” of fine dining, as well as the quality of the restaurant work environment from a mental health standpoint. Do you see your cuisine and business as opportunities to disrupt the model?

That’s a loaded question, especially coming from a fine dining background. There has been change, but it’s still a white-man-dominated industry, especially at the higher levels. There is the normal professional pressure to perform well and put in the hours the work demands and the stresses of the work environment. And then, when you see first-hand how some people are still treated within the industry…the racism—things I faced myself, especially being in cities that aren’t maybe as multicultural as Toronto, I’ve experienced, endured and witnessed those things happening to other people.

We had to stick together. I’ve seen that in the lowest and the highest realms and there was a breaking point in my career, where I felt I couldn’t stand that anymore. When I had to come back to Canada during COVID, I felt I lost part of my identity. That’s when I truly felt the pressures of the industry. That’s what brought me to The Burnt Chef Project, started by and for chefs and hospitality professionals to address mental health and barriers to wellbeing in the industry. Hearing their mission and what the different chefs on that platform have done to really change the landscapes they’ve worked in is a great model to move forward, and now I’m a Canadian Ambassador for the Project. These are things we really need to address—they’ve never been a priority. Not in my career, and arguably not in general.

MENU: It’s ironic that in one of the most connected, bonded and social industries, mental health has surged to the forefront of awareness. Are there specific features of the hospitality industry you feel have contributed to the prevalence of mental health challenges?

From the back of house to the people running establishments, people and teams have never been the true priority. Owners and managers need to understand that while they are hiring employees, these people do not actually work for you—in a sense, you work for them. Studies show that if you take care of the people that work for you and you invest in them and their well-being, they will be more willing to provide a better level of service, work harder, and enjoy coming to work even more. But, this is a competitive industry, with large egos. Some of these owners and/or leaders develop a superiority complex and think it’s a privilege to work for them—they take advantage of their workforce because of that.

There’s been an “army” mentality in place, where chefs talk down to their staff and

teams. Now we all know that’s not the best way to lead, but it’s been a broken system that repeats and is passed down as a sort of generational pain. That mentality needs to change or die out. Some chefs have changed their ways, and you can forgive, and you can even forget, to an extent. Others seem unwilling to change and are holding so tight to the past they’re holding people back. Unfortunately,

a lot of toxic stuff has come from that.

MENU: The Burnt Chef Project talks about stigma and the need for open dialogue and support for mental health in the workplace. What are your thoughts on how to eradicate the silence?

Hospitality and foodservice is an amazing industry, but I haven’t seen many other industries that disregard human emotion in this way. The idea that if you have stuff going on in your personal life, you need to leave it at the door is not realistic or fair. Those things stay on your mind and can really affect your behaviour or how present you are while performing your day-to-day tasks. We’ve been told forever to fight through the pain, but then you burn out or you cut or burn yourself on the job. That attitude forces things to clash on the job, and that’s part of why you see so many people burn out or even have mental breakdowns. So now, trying to create an open space where people can talk about what they feel they need to is new in this industry that’s pushed up against that for so long, but it’s crucial to create an area of safety, where people can talk about things in an open environment and access the support they need to guide them through.

I was made fun of as a kid drinking protein shakes post-service instead of having a couple pints of beer, and for heading to the gym at midnight after work—for living that kind of lifestyle. Now it’s trendy to take care of your health, but this is what we always should have been doing. Mental and physical health feed each other. This career is very gruelling for the body and mind, and people need to wake up to the effect it can have. If you’re not setting yourself up for success, you’re going to see that in your later years. Talking to some of the older chefs and seeing how their bodies and health have deteriorated by not really making these things a priority is devastating. I don’t want to be like that in my years to come, so it’s about putting in the work now and teaching others to make those things a priority for them. I hope more businesses will offer gym memberships instead of free staff drinks.

MENU: What about The Burnt Chef Project’s approach most resonates with you?

The interviews Kris Hall, the Project founder, was able to do with some of the top chefs in the UK were massive for me, and now they’re expanding around the world. Hearing about some of their challenges, how they’re trying to change the business for the better and what they’re putting in place to take care of not just themselves, but their employees gave me ideas I could bring into my own career and business.

The way those leaders’ experiences translate into the education the organization is putting out is so huge. A lot of people don’t understand how much sleep they should actually be getting or the type of food they should be eating to fuel their body or even, in an industry that’s been so tight on financial compensation, how to make finances work to our best ability.

MENU: You are clearly very ambitious, smart and courageous. As much as your personal experience coming out of the pandemic was devastating, do you feel that being forced to improvise, recreate and retool changed your path and perspective on what you want from your career?

To be honest, it would be a super easy decision for me to go back to Europe or to Asia and work at one of the best places in the world because I have the experience and passion to do so. But… I just believe so much in my vision here in Canada, and in this project—in having full creative freedom and offering that to people.

Coming back here and seeing how the Canadian food scene is evolving makes me want to be part of the change that our industry actually needs, whether that’s with The Burnt Chef Project or through the work I do with kids, trying to encourage the next generation to come into this line of work and how to do it in the right way.

I feel so many people have talked about the problems of our industry. Not enough people are doing anything about it. So as much as I’m building the Wanderlust brand and partnerships, a lot of how I’m doing things comes down to trying to be part of the solution. I understand some people might have larger operations than I do, but I’m working at the grassroots level on a weekly basis, talking to elementary, high school and now post-secondary students to really help them get started or guide them forward. Having a healthy place to begin with is the only way we’re going to really inspire the next generation.

MENU: What does “having a healthy place to begin with” mean to you, and what can operators do to attract and retain their people?

You might not bring home six figures doing dishes, but people who are appreciated and respected for the work they do and are compensated to a livable standard is the base of it. People don’t understand how far it actually goes to tell someone you appreciate the work they’re doing. If businesses are not doing that, we’re going to see a lot of changeover and closures this year, especially with the increases in day-to-day living costs.

The places that are putting their people first are going to do well and, when things do get better and we’re on the upswing, these places are going to absolutely blow up and flourish.

Chef Imrun Texeira has worked in some of the world’s best and most influential restaurants, including 3 Michelin Starred Noma in Copenhagen. Most recently, Imrun received the One To Watch award from Restaurants Canada. This award recognizes that in the development and progression of his career, he has

set a new standard of excellence for his leadership, creativity, and ambition.

He has also been named as a recipient of the Top 30-Under-30 Award for hospitality leaders in Canada and as a rising talent in North America by The Art of Plating.

Imrun was a semi-finalist on the Food Network’s Top Chef Canada Season 8 and a finalist on the Food Network’s Chopped Canada Season 3. Chef Texeira was also nominated for the Premier’s Awards: Most Successful Recent Graduate in 2016, which celebrates Ontario’s outstanding college graduates.

Instagram: @imrun.texeira | Facebook: @cheftexeira | Twitter: @imruntexeira | www.imruntexeira.com