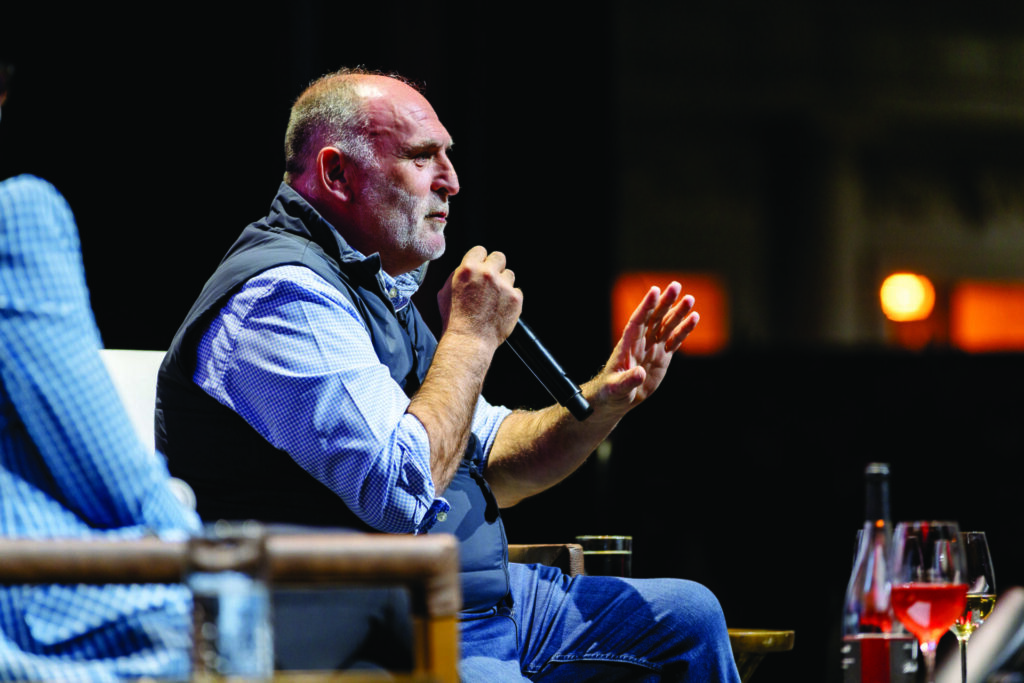

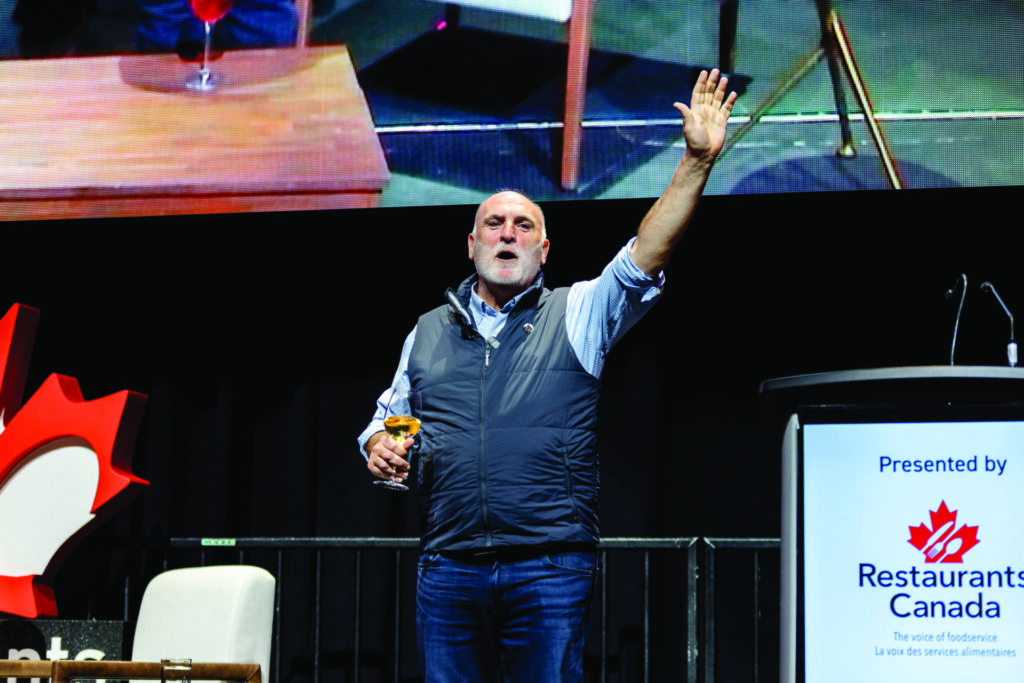

A Feast of Ideas: CHEF José Andrés at RC Show 2025

Presented by Restaurants Canada and High Liner Foods, the RC Show 2025 keynote unfolded as a compelling fireside chat between Chef José Andrés and Kelly Higginson, President and CEO of Restaurants Canada. What followed was an hour of candid, wide-ranging insights from one of the world’s most influential chefs, activists and thinkers.

Having recently spent six weeks filming a new show with Martha Stewart in Toronto, Chef José had taken time to explore celebrated local restaurants like Shoushin, Masaki Saito, LSL, and Actinolite, and paid visits to retail food haunts like The Cheese Boutique and St. Lawrence Market. But it wasn’t the shout outs to where he’d been or what he’d eaten that made the room lean in.

With humour, humility and conviction, Andrés spoke in stories—moments from his life that revealed deeper truths about the state of food, the restaurant business, and humanity. From learning to cook with imaginary shrimp in culinary school, to being told he wasn’t ready to stir the paella, to navigating the logistics of feeding millions through World Central Kitchen and when and how foodservice should think about showing up to feed communities, he painted a picture of a profession that is as fragile as it is vital.

What followed was less a prepared speech, but rather a series of bold ideas and vivid reflections—on food, on failure, on community, and on what it truly means to lead with purpose.

On finding lessons in the kitchen—and in the fire.

My mother was a nurse, and my father was a nurse. I was born in northern Spain in a region called Asturias—it’s very much like Canada. Very green, with a lot of lakes and rivers, though not as big as yours. I moved to Catalonia when I was five, so I guess I’ve been an immigrant all my life. Even though Spain is very small, Asturias and Catalonia could not be more different. Different language, different foods, different landscape, and different traditions.

I grew up watching my mum cooking from Monday to Friday and my father on Saturday and Sunday. My mother was more in charge of feeding the family, and my father was in charge of feeding the family along with friends and our larger family. So, my mum cooked for the few, and my father for the many.

My mum was a magician who could make anything from nothing—some flour, some butter, oil and milk to make a béchamel, adding any leftovers from the fridge. When the béchamel got cold, she’d make it into balls, rubbing them in flour, egg and breadcrumbs from stale bread. She’d fry those croquetas and my three brothers and I would be fighting for that one extra croqueta. She would always give it to the best-behaved brother that day. These were the dishes at the end of the month when the fridge at my house was very much empty. We were a working family, and we lived well, but at the end of the month, the fridge was empty.

I don’t remember any of the dishes at the beginning of the month—the steak or the fish. We were all waiting for the end of the month to eat croquetas. Now, my daughters all do the same.

Every time my father would make a big paella, I would help him with the fire. He would make a traditional paella with chicken and rabbit, but he never let me put the spoon in— I just helped with the fire.

One day I got very upset because I wanted to help with the cooking. He told me it was too windy, so I needed to help with the fire. I kept complaining, and he sent me away. I was 11 or 12 at the most and, when everyone was eating, my father pulled me aside. He told me he knew I wanted to do the cooking, and that that’s what everybody wants to do, but the most important thing in life is controlling the fire. It’s understanding and mastering your fire. Once you do that, you can do anything you want with your life.

This was a little lesson for a young cook in the making, but in a way it’s a metaphor for life itself.

On the people who shape us (whether we remember their names or not).

We all have mentors and people we meet along the way in our careers or maybe we read their book or see them on TV. We become who we become thanks to those people we have around us, even the ones whose names we’ve forgotten. Those who listened to us and let us know that we matter.

Obviously, I’ve been very lucky in my life. I’ve had many of those people. I have friends I began cooking with 37 or 38 years ago and we’re still friends. When I go to Barcelona, I can go to almost any restaurant and see old friends from school.

I went to a place called elBulli, and many of you will know Ferran Adrià. Ferran became everything to me. We are best friends today, but in the early days we were eight years apart, and when I was 16, eight years apart was a lot of years. I was very lucky to be at elBulli at the time he launched an entire revolution in new modern cooking.

To this day, Ferran Adrià is a brother, a father, a mentor, a chef—and not just to me, but to many. He taught me what it means to be generous. I remember the days when the chef had the recipes and wouldn’t let you see the book. But Ferran, from the very beginning, shared everything with everybody. Not just in the restaurant, but at conferences too. Every technique he developed, he shared with everybody. This is where I learned the importance of giving of yourself to others.

Culinarily, and in everything I try and do in life, he taught me to try and open myself up to everyone to help make everyone around me better. This is always something that will come back to you in good ways.

On survival, generosity, and the brutal beauty of the food business.

I think the most important thing for everybody in the food business is that your restaurant or business does well. Paying the bills is the most important thing. You don’t always have to focus on helping others, because just keeping your restaurant open or maintaining your farm is a miracle unto itself sometimes.

Food businesses are beautiful businesses, but behind the TV shows and the beautiful dishes, there is a lot of failure. I think it was Winston Churchill who said (or is credited with saying), “Success is going from failure to failure without losing enthusiasm.”

So, embrace the failure. It’s going to happen, and in a big way, but make sure that failure is not what brings you down, but what lifts you up. Do you know how many restaurants fail in the first year or three years? How many restaurants open and close each year in our industry? How many bills and salaries sometimes go unpaid? I don’t blame the profession I love. We are in one of the most beautiful businesses in the world. But it’s actually brutal.

You don’t have to support community with money or by doing a dinner to raise funds—just donate your time. Don’t do things that cost money when your business is having a hard time paying the bills. Your community needs you to be successful. That’s already amazing.

I was 23 when I arrived in Washington, D.C. I always saw nurses and doctors in hospitals as heroes because it always seemed they were doing more than necessary. We saw it during the pandemic. Generosity was everywhere.

Our profession is one of the most generous professions. Restaurants are always donating meals for people we don’t even know. If you feel you can, then do it. But the ways to give back to your community are plentiful, and most restaurants are already doing it.

On meeting your moment to serve.

There’s one great Ethiopian-born chef, who was adopted in Sweden, and ended up in America. He opened one of the most successful modern Scandinavian restaurants—Marcus Samuelsson. He’s a very talented chef. One day, he was a little bit upset with me because, once World Central Kitchen was founded, many chefs wanted to participate. I always told them, “Don’t worry. The day you need to participate, you will know it.”

I said this to Marcus numerous times, and he said, “Chef, it seems you don’t want me to help.” I said, “On the contrary. On the day you will be called to help, believe me, the energy you are going to have to put out is going to be so much. It’s okay that you are not helping right now.”

Then, COVID happened. Marcus found himself the lead chef doing hundreds of thousands of meals in the Bronx, and hundreds of thousands (that turned into millions) of meals in Newark, New Jersey. For him, and for many others in Canada and around the world, the moment will come. With World Central Kitchen, I saw the power of our profession. When there is an earthquake, you call search and rescue teams. When there is a fire, you call the firefighters. If there is an emergency, and people need to eat, who do you think is the most prepared? The restaurant industry.

During the L.A. fires, we had more than 80 food trucks ready to be deployed to any of the fires, to any of the shelters, to any of the neighbourhoods. We were using food trucks like fire trucks, but instead of stopping the fire, we were feeding people. We started this in Haiti in 2010, and in Ukraine we’ve done more than 300 million meals, in Turkey we’ve done 80 million meals, in Gaza we’ve done more than 110 million meals, in Israel we’ve done 3 or 4 million meals. In America, we’ve responded to every earthquake, hurricane and tornado in the last fifteen years. In Canada, we had a hurricane that made it all the way to Nova Scotia.

The need to serve communities is always going to be there, but don’t hurt your business to do it. Everything has a moment in life. First, make your business, yourself and the people around you successful. You’ll always find a way to give back, but the best gift you can give to your community, your family and co-workers is to become successful today.

Tomorrow is another day.

On fake shrimp and real lessons.

I left school when I was very young, and my father sent me to cooking school. It was a new school. You had to be 18 to join, but I was only 15 or 16. The school was private though, so they’d take anyone who would pay. But the school was not finished. In cooking class, we’d be at the table with pans and the teacher would say, “Okay, sauté the shrimp… Add the salt now.” But everything was imaginary. I was like, “What the heck is this s*&t?”

Every hour I had, I was working somewhere, whether or not I was getting paid. I’d cook anywhere they’d let me cook. I did military service, and they had me cooking for the admiral. When I came back from service, I was supposed to graduate, but I was tired of the fake shrimp. So, I failed three things: cooking, English, and accounting—maybe because I didn’t really go to any of the classes.

We need to control every dollar, and I wish I knew 30 or 40 years ago what I know today.

If restaurants fail, the entire food chain fails. The farmer fails. The fisherman fails. The employees and people driving the produce to the big city and import and distribution companies fail. Everybody fails. So, it’s vital that restaurants succeed.

How do we do this? We make sure we’re highly prepared when we open a business. Whether it’s a great hot dog stand, a food truck or a high-end restaurant, we need to make sure we put a lot of time into the numbers before we sign the lease. Very often, the failure of a restaurant lies in the fact we signed a lease the business cannot sustain. Even restaurants that have line-ups down the street can fail because the numbers were not aligned.

Learning about cooking, amazing produce, doing the best job you can—go for it. But make sure the numbers are sound and solid. That’s probably the most important thing I would do today if I could go back to when I was 16: spend the time to learn the numbers. If you don’t like the numbers, you need to marry the best CFO or accountant. I always tell people, “If you’re going to marry somebody, marry a chef. The next best thing is to marry somebody who knows the numbers.”

We have to make sure that the people who feed the world are able to feed themselves, for the well-being of everybody.

On redefining food as policy—and as a solution to everything.

For many years, I’ve been saying that food can be the solution to many of the problems every country faces. Food is handled by the Department of Agriculture (or what in America we call the USDA), but food is so much more than that.

Food is immigration, food is culture, food is defence and national security, food is science, food is history, food is urban housing development. I created two classes—including one with Ferran Adrià at Harvard’s school of physics, where we taught cooking explained through physics. Everything from roasting a chicken to making mayonnaise has a physics explanation. The second, A World on a Plate, teaches how food impacts everything from the environment, energy, health…everything.

We created the Global Food Institute at George Washington University, which is to start writing and shaping future policies where food is no longer the problem, but the solution. I began asking that every president of every country read a 1826 book by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste. Tell me what you eat, I’ll tell you who you are. He said that the future of nations will depend on how they feed themselves.

Not too long ago, the United States of America ran out of baby formula. That’s food. We say we have too much food and we have an obesity epidemic, but at the same time, we have a hunger pandemic in some parts of the world. We throw away food because we produce more than we consume. What happens if one day we wake up and we don’t have enough food to feed our country?

Recently, Japan had to release rice into the market because prices are going up because there’s not enough rice. Countries like Ukraine feed 500 million people, but they’re at war. We have typhoons, hurricanes, and droughts. We have pests. What happens if the perfect storm comes along one day and there is not enough food?

This is why we have to think about food differently and define our business within the policy of food. Good food policy will make every city better, every country better, and the world a better place.

*Please note this transcript has been edited for length and clarity.