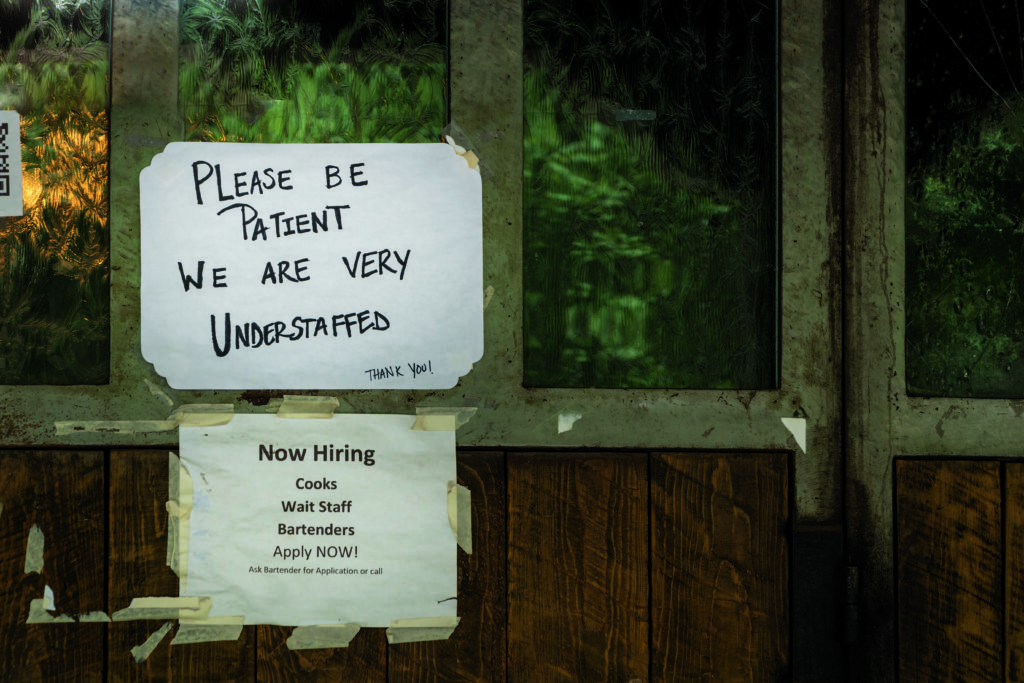

On the Foodservice Labour Shortage

In September 2021, the amount of unfilled foodservice sector jobs in Canada grew to nearly 200,000 vacancies. MENU reached out to Restaurants Canada’s Senior Economist Chris Elliott for a conversation on his thoughts on the labour shortage and what strategies, trends and tactics will matter most to operators now and in the coming years.

For foodservice operators desperate for solid information and guidance following an unprecedented string of industry-transforming changes, the struggle is real and immediate. So, while it’s fair to assume that discomfort with speculation is an occupational success factor for economists, there’s no denying that the inordinate amount of time they spend sifting through data in search of truth makes them an invaluable source of informed insight.

Chris Elliott starts with some level setting background. “We knew the labour shortage was going to be a long-standing issue when we look at the demographic factors – it was plainly obvious. In 2018-19, we could see the writing was already on the wall with the numbers we were seeing from Stats Canada. For context, back in the late 70s and early 80s, 15 to 24-year-olds accounted for roughly 20 per cent of the overall population in Canada, and that number has steadily declined to about 12 per cent right now. And, that number will continue to slide to about 11 per cent by 2030. The key issue is that young people generally account for about 40 per cent of all foodservice workers, so if you have that shrinking base, you’re going to have to make up for that somewhere else. We’ve also seen extraordinary social and cultural change with Millennials and Gen-Zs. Education has become more competitive, and consequently, younger generations are postponing entry into the workforce because they’re putting a lot more emphasis on school work, volunteer work and sports – they’re doing all they can to get into university.”

Elliott acknowledges that even though this statistical and social double-hit would have taken some ingenuity to overcome, the pandemic was an accelerant. “Immigration has always been a source for filling jobs. During the pandemic – especially in the early days – immigration numbers just dropped out. Now, there’s a bottleneck of people trying to get into Canada and an ongoing delay. I think though, that the pandemic has changed things in other ways. In the early days, we had two out of three foodservice workers either laid off and not working any hours or permanently unemployed.

That, I think, has led to a change where people are rethinking whether or not they want to rejoin the industry. They got a little bit of a break and found that they could spend more time with friends and family on weekends, whereas before they would likely have been working. There are all these different elements combining together and, as a result, we’re seeing staggering labour shortage numbers. These are numbers we’ve never seen before. It’s record-breaking.”

So many aspects of the restaurant business have changed it’s nearly impossible to know which problem to tackle first. While reopenings are long-awaited good news, many operators were surprised to learn that the teams they longed to bring back to work weren’t there anymore and debate as to why was rife. Elliott believes that many previous food sector workers have moved on to other industries looking for more job security because they were afraid. They may have been thinking, “Yeah, you’re reopening, but how long is that going to last?”

I think the pandemic has taken a problem and magnified it to a much bigger crisis than we thought could ever happen.Chris Elliott

Pandemic-era reporting, especially in the early days, focused a great deal on restaurants and other social businesses, which may have played a role in the loss of faith in the stability of restaurant industry employment. “I think there is some fear from the general public – you watch the news and when they talked about places you might catch COVID-19, it was usually gyms or restaurants that were speculated on in the news,” Elliott allows. “That certainly hasn’t helped the situation. In the new year, Restaurants Canada will be diving into Canadian households and Canadians, in general, to better understand how they feel about the industry. How they feel about having family members who work in the industry? Is there a different perception out there we’re not aware of? It’s an immigration problem, it’s a demographic problem, but is it also a perception problem? Is it something we need to get to the bottom of?”

There may be no single truth or absolute strategy to quell the labour shortage, but Elliott believes in the future potential of the industry and the certainty of its reinvention and revival. “Overall, the industry enjoys a very positive image – people love going to restaurants and having great food experiences. But we want to layer in the past and present employee experience for perspective. This is a very labour intensive industry and that’s not going to change. We can’t automate the way General Motors or Amazon can. We need to find a solution to this, but there’s no magic bullet. We need to look at immigration, we may need to look to older Canadians looking to supplement their income with part-time work in a social environment.”

Elliott also points out that the shortage is not concentrated in specific restaurant segments. The problems are more or less evenly distributed across all operation sizes, styles and locations. Some operators have made it through to this point based on their work culture, staying in touch with employees through the pandemic, offering them as much work as they could to keep them employed earning some income. This has clearly caught Elliott’s attention.

“There was a really interesting episode of The Decibel podcast on The Globe and Mail with an interview with a former foodservice employee, and they were quoting the numbers from the study we’d just completed. They were talking about free meals, benefits and similar tactics operators are using to try and attract new talent. They asked the former employee how she felt about those benefits and initiatives and she that while these are all good things to get people in the door, they cannot be temporary. These have to be permanent changes in order to keep people. So, I think there’s two elements to it – bringing people in and then retaining them in the long term. This is more expensive for the operator, but that’s the cost of holding on to your talent. I think it’s the future reality for sure.”

“What operators are doing now – working long hours themselves or cutting opening hours – those things are short-term solutions.” Elliott continues, “Operators and managers can’t work forever without burning out, and cutting back on hours is not a way to grow your sales. The industry runs because it has great employees, and that will continue. Offering some of these benefits are just the cost of doing business.”

Some restaurant brands are leaning into recruitment strategies that prioritize their corporate values and holistic employee value proposition. Elliott believes that hiring managers who rely solely on hourly wages and perks will not lead the labour solution. “Younger generations want to choose a company that knows how to relate to and support its workforce through corporate values. People don’t want to just work for a company, they want to work for something. If companies start to spread their values and what they represent, and employees understand how they make a difference in the world, that’s what will appeal to a younger generation. Putting those values forward – here’s who we are and what

we stand for, and here’s what we can do for you. Maybe it’s an experience they can take forward in life

or learning to ropes with intent to open their own restaurant. There’s got to be benefits both ways, and I also think there needs to be flexibility in terms of hours. It will take a combination of efforts.”

If labour were the only cost subject to sharp increases, restaurants might be able to scrape through; however, food prices, insurance, delivery fees, and rent are also skyrocketing in parallel. Elliott has clearly ruminated on exactly this. “Future success will likely come down to efficiency and productivity – is there a way we can reduce the size of our menu to earn efficiency in the kitchen? Do we shrink our real estate footprint and operate similarly to a ghost kitchen? Maybe we can use those efficiency gains to pay people more and not have to raise prices as much. Many restaurants are reformatting their footprint and there’s talk of some moving to take-out window service. I think many operators are looking at efficiencies that work for their brand and model.”

While agile thinking and efficiencies may help restaurants climb back into the black, what might they do to the culture of restaurants – their reason for being? If it’s all about ghost kitchens and condensed menus, what hope is there for the soul of the industry? Elliott is optimistic. “People still want to go out to restaurants. It’s the go-to place. The pandemic has changed how often and where people go out. Working from home has made some big changes. People aren’t going out for breakfast or lunch as much because they’re not commuting like they used to. These changes may have been caused by the pandemic, but I think a lot of them will be permanent. I don’t think we’re going back to five days in the office like we used to. The pandemic has changed things for certain operators based on where they’re located and how they operate, but I believe Canadians still want to go to restaurants and order delivery from a restaurant they could go to in person.”

The ghost kitchen model will play a growing role in the industry, but Elliott sees this as a natural disruption of the model. “Ghost kitchens will become a bigger part of the industry, but won’t replace the industry. People still want to go out and meet with people. If you have great food and great service, you can still do quite well. If you’re raising menu prices, I think there’s some “forgiveness” for that. People understand it. And, on the economic side, Canadians have accumulated about $190 billion in savings

throughout this crisis. There’s shopping power to spend, and I think a lot of it will end up in the foodservice industry.”

2 Comments