Sourdough: The Philosophy of Life in a Jar

Liesbet Vandepoel likes to think of a household’s sourdough as an extension of the family. Like a pet. Afterall, it is a living, ‘breathing’ organism you feed, grow and care for. So maybe she isn’t far off.

Vandepoel works for Puratos, which provides ingredients (everything from glazes, to yes, sourdough) to foodservice and hospitality businesses. Puratos developed the Sourdough Library in St. Vith, Belgium – a repository for more than 100 sourdough cultures. There, these cultures are studied and archived as a time capsule of our past so we can preserve a diverse future.

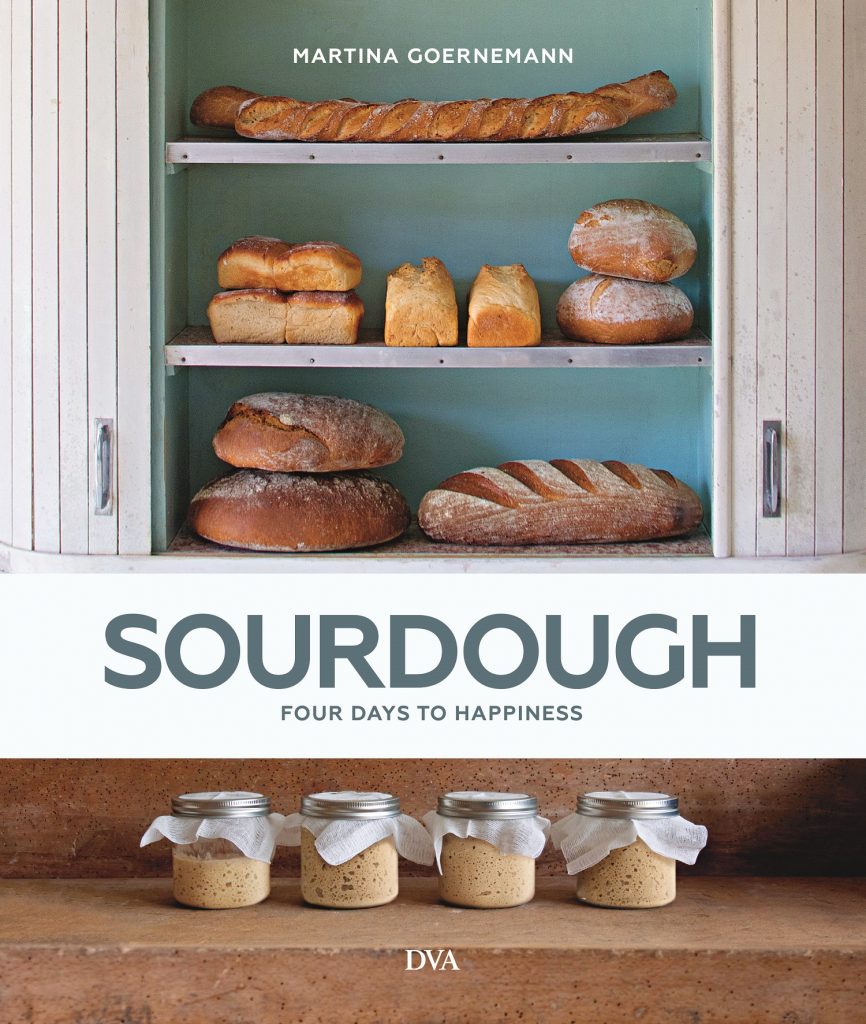

Recently Puratos joined forces with writer Martina Goernemann to produce ‘Sourdough: Four Days to Happiness’. The cookbook details the journey of a sourdough starter across different locations. As it makes its way to various families and individuals, the sourdough is transformed and interpreted in different ways.

Why is sourdough so important?

One of the magical things about sourdough, according to Vanderpoel, is its ability to tell a story. The changes are tracked through the dough, and connections are formed. There’s a passion and emotion captured in the bread – considering the love and attention that was required for it to come to be.

This idea provided the basis for the book, which is divided by story (each person who has touched the bread has their own section) and broken down using titles inspired by their sourdough’s journey.

If, like me, you grew up on Wonder Bread, the importance of sourdough may seem a little out of reach. It’s not easy to grasp the historical context of sourdough. In fact, one of the oldest sourdoughs dates back to 3700 BCE!

On a global scale, as humans moved across the globe, adventuring and settling in new areas, sourdough was pivotal to their survival. Early settlers in the Western United States relied on sourdough to produce bread when yeast wasn’t available (1).

Vanderpoel uses the example of immigrants traveling from France to San Francisco during the Gold Rush. French families brought with them their sourdoughs, and with the change in location, came a change in microcosm. The sourdough was altered, creating the San Franciscan sourdough we know today.

What makes a good sourdough?

Vanderpoel is quick to point out that though ‘sour’ is in the name, this doesn’t mean that sourdough is always sour, or that the more sour a sourdough is, the better. Of course, we look for a sourdough with high acidity and with a pleasant perfume, but different sourdoughs from different regions take on a different taste. Take for instance the semolina from Italy which has a nutty, clean, and sweet taste.

The way sourdough is best enjoyed is a subjective choice. A good sourdough can be delightful with a little butter or olive oil, warmed, and accompanied with a glass of wine. Of course, Vanderpoel points out that the best way to enjoy sourdough is in good company, after all, this has historically been a food that was made to be shared and bring people together.

What does sourdough means for consumers and foodservice operators?

With the popularity of low-carb, keto, or gluten-free diets, interest in bread had waned. However Vanderpoel believes that by offering an alternative to the popular diet books, a cookbook that celebrates bread and gluten as an educational piece, the public will gain a better understanding of what sourdough is, and what is means.

In fact, Vanderpoel believes that there is a recent increase in customer’s interest in sourdough bread, citing the increase in skepticism and increase in the interest of locally sourced and sustainable food. According to research from Restaurants Canada, eight out of 10 foodservice business operators across Canada now say environmentally sustainability is important to their success. Among the hottest trends at restaurants are locally sourced foods, sustainable seafood, and more environmentally-conscious single-use items (2).

Customers want to know what is going into their food. They’re critical and looking back to more traditional processes and methods that they deem ‘healthier’. They don’t want bread sourced from a manufacturing plant, but rather, homemade bread, created with local ingredients.

Vanderpoel’s advice to foodservice and hospitality operators is to leverage this enthusiasm to help your bottom line. A basket of complimentary bread is an expectation for some customers, but Vanderpoel rejects this idea. Vanderpoel points out that seeing bread as a ‘freebie’ takes away some of the value of bread. With other fermented dishes like beer, or cheese, customers happily pay – so why shouldn’t sourdough be as valued?

How can sourdough play a role in your restaurant?

When asked if there is a specific quote from Sourdough: Four Days to Happiness that Vanderpoel particularly resonates with, that encapsulates what that magical quality of sourdough is, she says, “Sourdough is the philosophy of life in a jar”.

Sourdough requires care, it takes time to develop, and it changes over time. It’s also not always a given – without the right elements, sourdough won’t survive. The effort that goes into producing a sourdough says a lot about the care and quality you provide your customers. As we become busier and life becomes more hectic, taking the time to not just make, but also savour sourdough is a special moment.

Serving up an exceptional customer experience is so important as it sets you apart in a saturated market place. Creating an atmosphere, with help from sourdough, of warmth and welcoming is an essential part of customer service. Consider breaking bread with your customers over a toasty loaf of sourdough – after all, as Marcus Mariathas from Ace Bakery puts it: “Bread makes everyone happy!”