The Cauliflower Game

Wild weather and riding out the food pricing storms

In 2011, a high-pressure system developed off the west coast of the United States. The system was caused by a La Niña event, and it triggered the worst drought in California’s recorded history. The drought crippled California’s agricultural health and created lasting damage on the trade economy of one of the biggest growing regions in North America. This is when cauliflower started to make headlines.

El Niño and La Niña are cyclical meteorological phenomena caused by oceanic and air mass interactions and are collectively labelled El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). They are characterized by warming (El Niño) or cooling (La Niña) trends that can have far-reaching effects on growing regions around the world. The high-pressure system that occurred in 2011 was caused by the descent of cold air towards earth’s surface. The same cooling trend that caused drought in the southwestern United States also created drought conditions in East Africa and flooding in Australia. Canada is California’s largest importer of agricultural goods, so it’s not surprising that when production went down, prices north of the border soared.

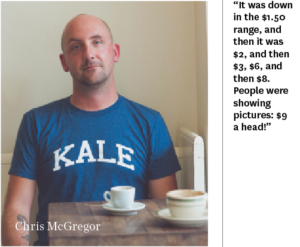

Chris McGregor owns and manages a produce supplier in downtown Toronto: Romano’s Fresh Produce, Inc. He got into the business last year, after spending years working as a chef in some of Toronto’s hotspots, including the Auld Spot Pub and 416 Snack Bar. His entrance to the produce industry happened at what he considers a key time as far as ENSO goes. “Everyone in the supply chain was affected by what was happening,” he says. “It was really weird to watch it happen. All the guys down at the terminal who have been doing this for years were losing their minds at how prices were climbing.”

What produce was most affected for Canadian buyers? “Greens,” says McGregor, “herbs, citrus fruits, tomatoes, cauliflower. The ‘cauliflower game’ that happened last fall, it was crazy.” McGregor says. “It was down in the $1.50 range, and then it was $2, and then $3, $6, and then $8. People were showing pictures: $9 a head! When one guy saw that another guy couldn’t sell it, he jacked his price up. And when supply dried up, they started bringing it in from Europe.”

According to statistics released by the California Department of Food and Agriculture in 2014, revenue from cauliflower production decreased by almost 25% between 2010 and 2012. Tomato revenue went down by nearly 40%. Across the board, income from all vegetable crops grown in California decreased by over 3% during the same period. “As a small business owner who wants to provide his clients the best possible prices, it sucks,” says McGregor. “It sucks to have to go to a chef who orders the same thing every week, and each week the number on the invoice goes up and goes up. Clients were frustrated at vegetable prices. But they knew that I had no control over it.”

California exported 11% fewer oranges and orange products to Canada in 2012 compared to 2011, 6% less garlic, and 9% fewer carrots. With La Niña coming to a close with a warming trend this past winter, some of California’s precipitation is returning, but McGregor points out that this doesn’t mean prices will be back to normal anytime soon.

“It has had a trickle-down effect,” he says. “You would think because La Niña passed, prices would go back down, but it’s had a lasting impact on the pricing. It’s like people are realizing that even though the situation isn’t as dire this year, maybe it could be next year or the year after. I think what it’s done is make the entire industry step back and look at themselves. There are whole farming networks that went completely out of business.”

Ontario has seen significant decreases in crop yields in the last 24 months, with cauliflower yields down 24%, cucumbers down 28%, and peaches down 15%. British Columbia saw cranberry yields drop almost 30% and some grains, like malt, suffered a 19% decrease in totals produced over the last year.

When demand exceeds supply here, Canadians look to their southern neighbour for exported goods, but a moderate La Niña is expected to take hold this fall, which means the return of extreme drought in America’s southwest is a possibility. With waters just beginning to recover there, it would be a huge hit to agriculture and exports.

“People still have to recoup their losses from last year,” says McGregor. “The only way to do that is to keep your prices elevated this year, and maybe next year, and maybe the year after. By the time you’ve recouped your losses, whatever insurance didn’t cover, you have to think, this might happen again.”

If extreme weather becomes the new normal, both farmers and consumers need to start making plans to deal with the effects. As McGregor reminds us, it is in nobody’s interest to play the “cauliflower game.”